(Photo credit F Romberg)

Francesca Romberg, Social Media volunteer for BPEC recently took the Ferry to Calais hoping to lend a hand in the Jungle and Dunkirk migrant camps. On her return she gives her impressions.

25/03/16 F Romberg (R Freeman eds)

On Saturday at 3am we left the University of Sussex heading to Calais. As drunken revellers roamed the dark streets around us, we filled the car with donations from the Hummingbird Project and a healthy dose of nerves and anticipation. We were going to help, as so many British people have before us, in any way we could. For us, one of the most important purposes of our journey was simply “to bear witness”. To see the realities of the camps, to let the people there know that we care and to let governments know they cannot get away with this, to hear the stories of those willing to talk and to spread the word back home.

The camps in Calais and Dunkirk are supported almost entirely by British and French volunteers, giving time, money and great effort. We joined them, aware of the preposterous lack of proper support from the UK and French governments, big NGO’s such as the Red Cross and Oxfam. The only signs of official representation were the hundreds of riot police in Calais - the notorious Compagnies Républicaines de Sécurité- and the tall, white, barbed wire topped fences paid for by UK taxpayers.

On arrival we call in at L’Auberge/Help Refugees warehouse. Here volunteers work like ants to provide aid. Most of the jobs there anyone can, and will, do. We find this out quickly as we chat to other volunteers from incredibly diverse backgrounds. We sort through donations; checking they’re fit for purpose, negotiating a maze of boxes to find the right storage place. The pile of clothes seems never ending; people have been generous - 2 weeks ago the warehouse was practically empty. Food bags and hygiene packs are put together to be sent out into the camps. In the kitchens, run with military precision by professional chefs, volunteers busily chop and wash-up preparing to feed over 2000 people a day.

After two days working in the hive-like warehouse, we head into the camp known as The Jungle.

The first thing to hit is the smell. The fumes from the nearby chemical plants are one of the many reasons the Jungle is completely unfit for human habitation, they cause many camp residents to suffer serious health problems. As we enter the destruction caused by the evictions that took place only a week before is plain to see. Shelters torn down and belongings left strewn across the site. Clothes, toys, books, food, blankets, all left behind - a testament to how little warning was given. The only buildings still standing in this half of the camp are community spaces - a church, a mosque, a youth centre, the Hummingbird Project’s Safe Space, Jungle Books (a community library and language centre) and the information centre, where the Iranian men who have sewn their lips together, protesting appaulling camp conditions are housed.

But beyond this there is still life in the Jungle. There is the highstreet. Shops, restaurants, and shisha bars are all open, we talk to everyone that we can. Give someone a smile and a greeting, and they’re often extremely happy to talk to you along with much tea and hospitality. We chat about life in Brighton, life in the camp, how long people have been here, why they want to cross the channel. Mostly it’s about family - mothers, brothers, fathers, children who live in the UK. This simple human connection is one of the most powerful aspects of meeting these people, one which is entirely overlooked by statistics, and political and media rhetoric.

Chatting our way around the camp we meet several boys in their early teens, mostly unaccompanied. It is impossible to fathom how these young boys have made the journey alone and on foot from places as far away as Afghanistan. The Jungle is an unbelievable place for anyone to live, but in leaking shelters, with little warmth and nightmarish sanitation, surrounded by highly dangerous crime and heavily-armed people-smugglers, these boys are making their way into adolescence.

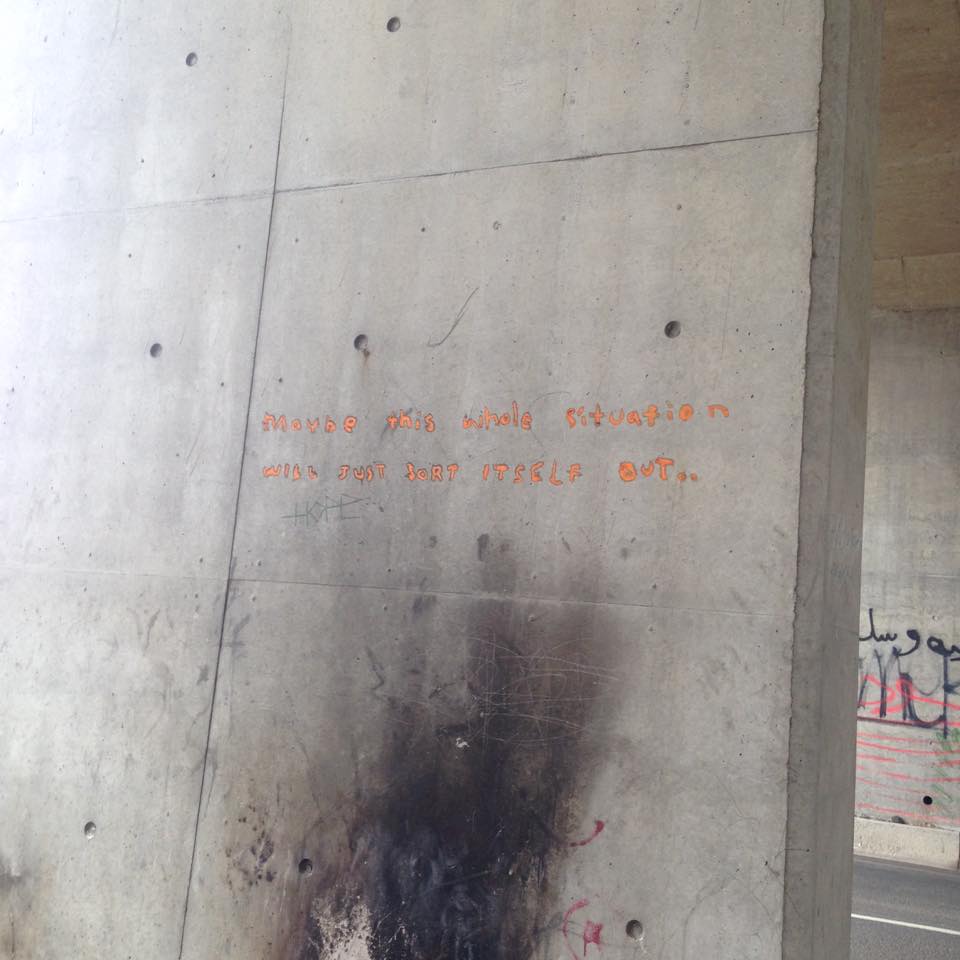

With the recent destruction tensions are higher than ever as the conditions become more cramped. A terrible fight over a five Euro bike a few days before had resulted in a man having to be hospitalised. The legal centre had been burnt down in dubious circumstances, but it’s rumoured fascist far right groups could be behind it. As we headed to the local supermarket, just five minutes away, to pick up dinner, its cleanliness and orderliness illuminated by strip lights felt a world apart from where we had just been.

(photo credit F Romberg)

The Jungle cannot be ignored any more. Fences and police are not working. These people need love, compassion and real action. What is the point in having a life of comfort and security, if those down the road from us do not? Humanitarian aid is just a sticking plaster, hiding the issues at play here. The Jungle is the manifestation of the disastrous effects of colonialism, globalization, greed, war and inaction from global leaders.

Humanitarian aid is just a sticking plaster, hiding the issues at play here.

The following day we went to Dunkirk - a completely different story. The local Green Mayor has defied all odds and tried to create a camp which is fit for purpose, buying local farmland with dreams of warm shelters, schools and communal areas. But bulldozers closed in on the Jungle and in just three days they had to rush to prepare the camp for its new inhabitants.

The difference is instantly apparent; no makeshift shacks or leaking tents, no oppressive police presence, no piles of rubbish, putrid green pools of pollution or foul smells from poor sanitation and noxious chemical plants. Children cycle around on bicycles, purpose built wooden shelters decorated with little fences, or posters, fly Kurdish flags (the majority of the residents at the Dunkirk camp are Kurdish people from Northern Iraq) and the ground has been flattened and gravelled to minimise flooding.

Stationed in the women and children’s distribution centre for the day, comprised of brightly painted shipping containers, we are opposite another container to be turned into a communal kitchen. Our coordinator told us, “This is not a beggars can’t be choosers situation. These people have had their human rights violated repeatedly. If we can give them something they want, then hell yeah we will give them what they want.” Unclean, ripped or broken donations are kept back. This ethos of providing dignity as well as aid is uplifting to see. Throughout the day women and children come in looking for clothing, soap, baby wipes and formula and we do our best to provide. Smiling, kind, friendly and polite, some look through the boxes of clothes and try things on.

This is not a beggars can’t be choosers situation. These people have had their human rights violated repeatedly. If we can give them something they want, then hell yeah we will give them what they want.

On the day of the terror attacks in Brussels we are outside, enjoying the sunshine, chatting and playing with the children. A man comes up to us and insists on giving us a big bar of chocolate and a badminton set for the children. His people, the Bedoon, are from Kuwait where they are not legally recognised by the state. Bedoon are not entitled to the same rights as Kuwaiti citizens, despite making up 40% of the army. He wants to move to England because people there understand the situation of his people better than in other countries. His English, learned from films and a dictionary is very proficient. He offers truly sincere condolences to our Belgian colleague. Talking to him, hearing his story and seeing his kindness is truly humbling - if anyone can empathise it is the residents of these camps.

The conditions in Dunkirk are far better than in the Jungle, but still, it’s by no means perfect. It cannot accept many more people, internal politics of running the camp have created difficulties and there is still a lack of professional support. Above all, it is a refugee camp, not a proper home.

(photo credit F Romberg)

On our way home we drive through passport control. We are ushered through with nothing but a smile, a glance at our passports and a quick check of the car boot. We remember the friends we’ve made. The ones who would be resting now after a long night of facing riot police, tear gas, fences and barbed wire for a chance to get to the UK. Even if they make it, their problems are far from over. In the UK they face destitution, squalid housing, drawn out asylum claims, people who prey on the poor and vulnerable, racism and the horrors of prisonlike centres where they can be detained for an unlimited amount of time.

Sitting here, recounting this, I think of all the times I’ve moaned about the UK- the weather, the government, the people, the mundane British lifestyle. Yet for many of the people I met on the border it is their dream. Of all the thoughts and feelings my time there evoked, the most pertinent was the amount of privilege we have. Privilege granted for no reason, it’s just the place we were born and the luxurious rights that it affords us.

If Fran's story touched you and you would like to lend a hand feel free to click the links below.

http://www.hummingbirdproject.org

http://www.helprefugees.org.uk

https://brighton-and-hove.cityofsanctuary.org

http://brightonvoicesinexile.co.uk

https://www.facebook.com/brightonshelterbuildproject/